Birders of a feather flock together at Marks Cove

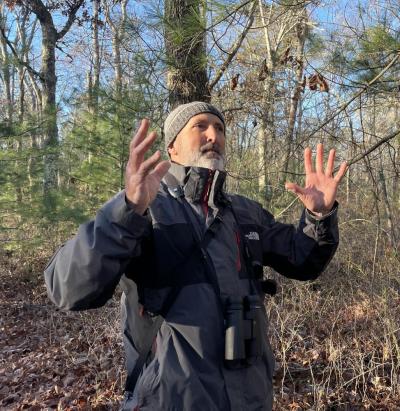

A camera the size of a Gatling gun strapped to his side, Mike Tucker crunched through the fallen leaves of Marks Cove Conservation Area, headed towards the water. The only sound that could be heard were wet shoes squelching on slippery wooden boards in the cold, bright air, but expert birdwatchers like Tucker know to listen for more than that.

“Carolina wren in the distance,” he said. “I heard a house finch in the distance as well. And the steady hum of traffic.”

On the morning of Sunday, Dec. 4, Tucker led a handful of intrepid birders through Marks Cove. The event, the first in the Wareham Land Trust’s Winter Wonder series, was officially called Winter Bird Walk. Tucker suggested a different name: “Tailing along with the bird nerd.”

“Nature doesn’t stop existing in cold weather,” he said, “and it can be fun to see how things change. How birds and wildlife adapt to cold weather. If you know what to look for, you can find some cool stuff.”

Tucker has never stopped looking. He has studied birds since he “was a wee lad.” When he was three years old, he would stare endlessly at the woodpecker that flew over his playpen.

“They couldn’t pull me away,” he recalled.

He got his first field guide when he was 10.

“Back then, parents weren’t worried about a fifth grader walking in the woods by himself,” he said.

Since then, his life has been an “ongoing battle” between preserving his beloved birds and the forces of habitat loss, invasive species and a booming predator population. He said that if it was 1987 all over again, he would blast bird calls on his boombox.

Tucker can imitate the calls of various species with uncanny accuracy. His song caused the fluffy little chickadees to dart across the branches above, hovering over Tucker as he looked up in rapture to meet them.

“I’ve seen a lot of birds over the years,” he said, “some fancy ones, and people are always surprised when I say the chickadee is my favorite bird. I just love them. You can always count on them.”

He imitated the sound of a screech owl, the chickadee’s natural predator.

“That really gets them going,” he said. “These chickadees, boy…”

“We thought that was actually an owl,” said Wareham Land Trust Board Member J.C. Weber. “We thought, ‘Why isn’t he talking about that owl?’”

“Can you do it again?” Asked Susan Mann, astonished by his abilities.

Tucker said that it’s easier than it looks.

“If we all do it,” he said, “we’ll call in birds from all over Wareham.”

He can even imitate the sound of an injured squirrel or rabbit.

“I’ve had barn owls land within 50 feet to that sound,” he said. “They’re fun birds, they’re so curious.”

Tucker identified and shared knowledge of every bird and plant he saw, stopping his flock with a single raised hand and a brandish of his binoculars.

“Robin,” he said. “Oh, there’s a brown creeper on that tree there… I heard an eastern towhee doing a note back there.”

Coming to the end of a maze of pointy trees and thick brush, Tucker reached the water’s edge at last. Standing on a dense, mucky floor of salt marsh grass, the sun blazing, he admired the plants’ triangular stems.

“It’s pretty,” he said.

He spotted “a good-sized woodpecker” and an osprey nest in the distance.

“Each generation of young that comes to nest,” he said, “they’re looking at telephone poles, not trees.”

He has seen several ospreys die from coming in contact with those poles.

On the way back, Tucker spotted some ruby-crowned kinglets, among the smallest birds in the world.

“They are just so stinking adorable,” he said. “They’re these cute tiny little things.”

He also saw some thrushes, and delivered a small-scale lecture about them.

“Anyway, I’ve rambled,” he said.

He went back to doing bird calls.