The life and times of the wily coywolf

They don’t howl at the moon. The males are attentive dads. And they aren’t “pure” coyotes.

Jonathan Way spent 90 minutes Saturday educating more than 50 people about the life and times of the Eastern Coyote, known more precisely as the “coywolf,” in a presentation sponsored by the Wareham Land Trust.

The Barnstable-based Way, who earned a coyote-based doctorate from Boston College and has written two books on the critters, is definitely an admirer of the smart, adaptable predators who now frequently call suburbia home.

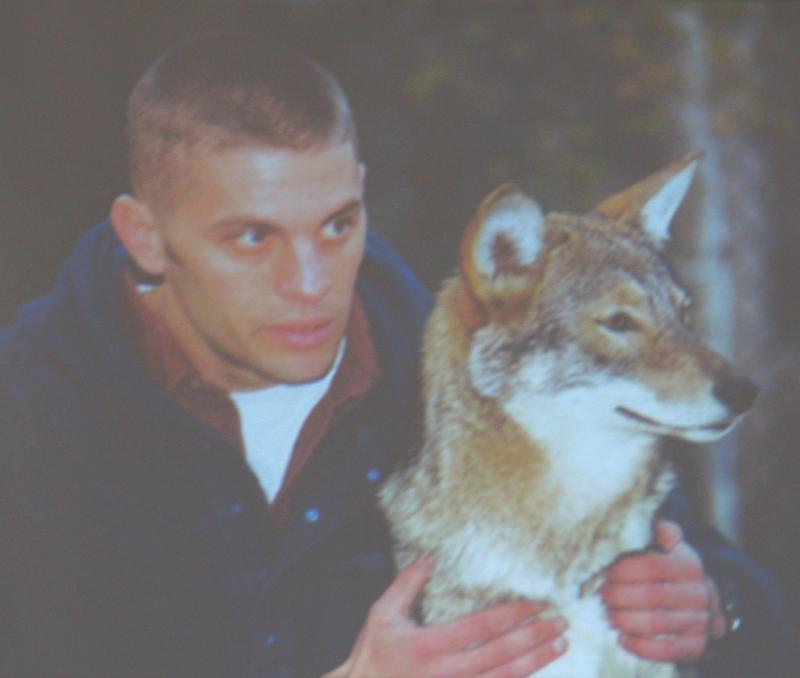

He raised a group of coywolf pups whose home is now the Stone Zoo in Stoneham and has studied coyotes on the Cape and in the relatively urban area just north of Boston.

Here are some of the things Way had to say:

They’re hybrids. What we know as coywolves are, genetically, about 60 percent western coyote, 30 percent eastern red wolf, 10 percent domestic dog. The hybrid first emerged in Ontario, Canada, in about 1919 and spread southeast into the northeast United States . . . arriving in Southeastern Massachusetts in the 1980s and ‘90s.

Why they howl. Not because there is a full or moon or because they want to scare people. Mostly to mark their territory or “rally the group.” Sometimes because “they enjoy it. Why do people sing?”

Puppy training on the bog. Pups are born in late March or early April in dens dug under fallen trees or into hillsides. In June, “about the time school is out,” the young families emerge to “rendezvous sites” where the growing pups are trained in the ways of coyote-dom by Mom and Dad. Cranberry bogs make ideal rendezvous sites or “puppy training centers.”

Ten to 15 miles a night. That’s how far a pack of three to four eastern coyotes typically travels when out and about. Some coyotes have been known to travel as much as 50 miles in a day. That, more than any coywolf population boom, explains “why it seems they are everywhere.”

How one studies coywolves. Way and other researchers trap coyotes (in large wire-mesh traps in which a door shuts behind an animal entering to get the bait), take their measurements and a sample of DNA, attach radio collars, and release them unharmed back into the wild where their activities can be tracked using the collars. The collars are “24/7 data banks.” Without collars, “it’s just anecdotal information.”

Trapping is difficult. It takes a lot of patience and good supermarket meat to lure coyotes into the traps. On average, it takes four to five traps set every night for a month to capture one wily eastern coyote. Other species are not so trap-shy. In his slide presentation, Way documented some “non-target captures:” raccoons, foxes, crows, seagulls, a Labrador retriever.

Killing them doesn’t decrease the population. Although it is legal to hunt coywolves in Massachusetts from October to March, killing some coyotes does not decrease – and may even increase – the population. When a pack leader is killed, another animal steps up to fill the void in the territory. Or, in one case observed by Way, the highway death of a pack leader resulted in two younger animals splitting the territory and developing two separate packs. Overall, Way described the coywolf population in the areas he has studied as “stable.”

If you are afraid of coyote bite . . . Consider the statistics. There are about 4.7 million dog bites reported in the United States every year, with 15-20 resulting deaths. There have been only five coyote bites in Massachusetts history and only two human deaths due to coyotes in North America – ever.