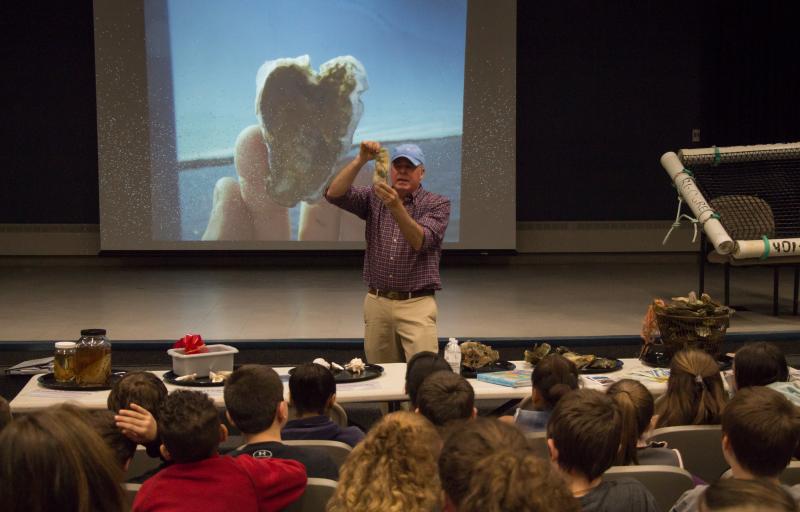

Students see a man about a bivalve

Students at Wareham Middle School watched as the sun-reddened man at the front of the school’s auditorium held up a cluster of oyster shells, which had grown together like an unusual rock-- or, according to him, like a sprouted Chia pet.

“Are you guys too [young] to know what a Chia pet is?” Steven Patterson, Shellfish Manager at Rhode Island Oyster Gardening for Restoration and Enhancement (RI-OGRE), asked, referring to the terracotta figures used to grow chia seeds.

Patterson introduced his organization during the talk about the endangered wild oyster, saying that the program is “a citizen-based approach to bringing wild oysters back to Rhode Island.”

“And the citizens that volunteer with us like to be called ogres. Must like ‘Shrek,’ I guess,” Patterson continued, eliciting some giggles from the students.

The meat of Patterson’s 50-minute talk wove in basic oyster biology, and how to recognize a wild oyster, while focusing on OGRE’s work to rescue the wild oyster, as well as the environmental importance of oysters.

“One of the reasons oysters are what we call a ‘keystone species’ within the estuary is because they ... have this amazing ability to filter water,” Patterson said. “They can filter more than 50 gallons of water, per oyster, per day.”

But, despite this ability to filter water, said Patterson, certain areas of Rhode Island are currently closed to shellfishing, such as the Navy base in Newport, and the Providence bay area. According to Rhode Island’s Department of Environmental Management, this is due to concern over human consumption of shellfish from polluted waters.

“Even though my oysters are for habitat restoration, and not for human consumption, I’m not allowed to put my oysters, or have any ogres in areas closed, due to pollution,” Patterson said.

Patterson also included a slideshow in his presentation, allowing the students to see the microscopic, clear zygotes oysters begin their life cycles as, all the way up to fully mature oysters, some of which were 10 inches long. Growing and older oyster clusters, Patterson said, provide good hiding places for fish, as well as feeding grounds for herbivorous shrimp that feed on the algae growing on the oysters’ shells.

Patterson said he thought the talk went well, and was pleased with how many students engaged in it, despite it being near the end of the school day.

“If we’re going to save the wild oyster, as an endangered species, we need to make sure the general public is educated in the first place about what a wild oyster is,” Patterson said. “They won’t know how to protect them, if they don’t know what they’re looking at when they see one.”