Teaching history as it happens

For the past year or so, it has often felt like Americans are living through one historic event after another. Few people know that better than the Wareham High School teachers tasked with educating the town’s curious young adults.

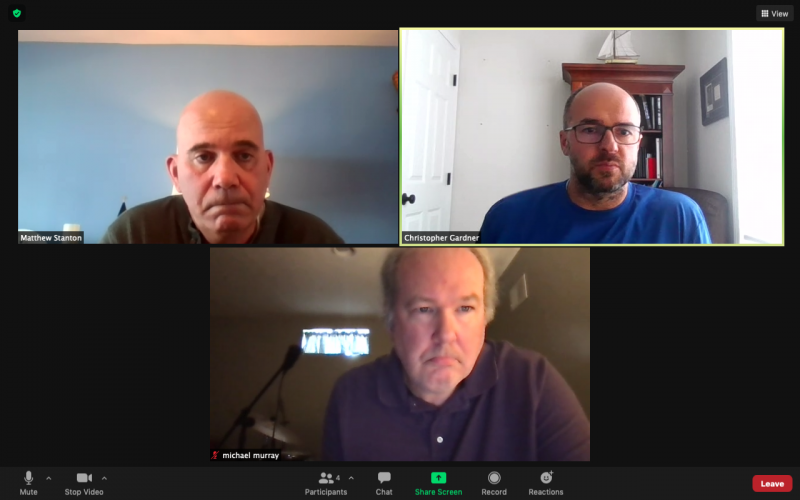

Between the pandemic, the 2020 presidential election, the angry mob that attacked the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6, the inauguration of President Joe Biden and the ongoing second impeachment of former President Donald Trump, there has been plenty to discuss, according to three high school teachers.

“It is exciting, because there’s no shortage of things to talk about,” said Christopher Gardner, who teaches world history, U.S. history II (honors) and a contemporary affairs class at the high school.

He said that his goal is to have discussion points ready for the topics that come up. But ultimately, Gardner said, he thinks his job is to “facilitate discussion amongst the students” because he feels that’s how they learn best.

Michael Murray, a history and English teacher who is also the chair of the humanities department, emphasized that much discussion of current events is student-driven.

“The student inquiry piece is really what drives it, not just in history but really in all the subjects,” Murray said.

In English, for example, he said students write research papers — often about a controversial topic that they can choose based on their interests.

“There’s zillions of opportunities for kids to find out what they want to know more about, or need to know more about,” Murray said.

While it has been especially evident recently, Col. Matthew Stanton — who teaches Junior ROTC, AP American Government and the International Baccalaureate program’s Global Politics course — said there has always been “plenty to talk about” in terms of historic events.

Stanton said he loves how students will make connections between current events and things they learn in their history classes.

“There’s a lot of talk of impeachment and how President Trump was the first president ever to be impeached twice, right?” Stanton said as an example. “But what does impeachment really mean?”

Stanton said some students might come to class thinking an impeached president is immediately removed from office, and that provided the opportunity to delve into the procedural specifics. He said he encouraged students to draw off of history, while also looking at their textbook and the Constitution.

Gardner said his students were really engaged in the election process and had plenty of thoughts on each state’s approach to voting and counting ballots. Once the election had largely passed, students turned to other topics.

“I have never had the 25th Amendment come up in class before this year,” Stanton said, as a more recent example.

As students read through the Amendment, Stanton said they quickly came to the conclusion that there wouldn’t be enough time to invoke the 25th Amendment before inauguration day.

“They came to their own conclusion based off of what they read in a document that the founding fathers wrote, what, 250 years ago?” Stanton said with a note of pride in his voice.

Gardner said he’s quick to shift gears from a planned lesson when it’s clear students want to talk about an event, particularly with his contemporary affairs class.

“If there’s kids talking about it, I’m dropping everything,” he said. “If kids are talking, I’m like, ‘yes, let’s do it.’” Gardner said it can be especially hard to get discussions going with half the class on Zoom and half the class participating in person, so those opportunities are crucial.

Gardner and Stanton both said upperclassmen are often more likely to be closely following national news or politics. They’re the ones beginning to form their individual beliefs through inquiry and discussion.

“Eighth graders — they’re coming in, ‘this is what my parents say; this is kind of what I think,’” Stanton said. “But by eleventh grade, they’re saying, ‘well wait a second. I think I’m thinking in this direction.’ And then they’re bouncing it off their classmates informally.”

Gardner added that he thinks it’s important to encourage students to do their research and be open-minded.

“It’s OK to disagree,” Gardner said. “Sometimes that brings tension and heated moments, and that’s OK. But I think the biggest thing is just to make sure you’re getting information from more than one source sometimes.”

Murray agreed, noting that students benefit from the hours they spend in an academic setting. He said teachers are particularly equipped to teach students how to “inquire effectively.”

“I want people to know things, and I want them to have the skills in order to acquire that information and to communicate it,” Murray said.

But with all the opportunities for learning, living through history can also take its toll on students, Stanton noted.

“Sometimes the news can be so overwhelming and so negative [...] I think we like to, from time to time, have them take a step back and say OK let’s look at this from a positive point of view.”

Stanton said sometimes that means saying, “Let’s look at how resilient the longest-surviving Constitution in the world is” or pointing out the ways the country is still moving forward, despite differences in opinion.

“Especially when you see numbers night after night with this pandemic, it definitely takes a toll on students at this age,” Stanton said. “In terms of [teachers’] role in this, I think it’s really important that we continue to emphasize the positive and how we will continue to keep moving forward.”