'Tis the season to be aware of Lyme disease

The sun is shining and nature is calling, but the warm summer months also brings a concern for residents of Massachusetts: Lyme Disease.

Lyme disease is a condition that is no stranger to Massachusetts residents. In 2005, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, "Massachusetts had the 4th highest incidence rate of Lyme disease nationwide," at about 36 new cases per 100,000 people.

Lyme disease in Massachusetts is spread by deer ticks which are most numerous in brushy, wooded, or grassy habitats, according to the Department of Public Health.

The wooded and marshy areas of Wareham are therefore a well-suited environment for ticks, giving more reason for people to protect themselves this summer season, said Wareham Health Agent Robert Ethier.

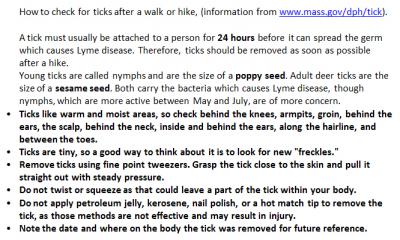

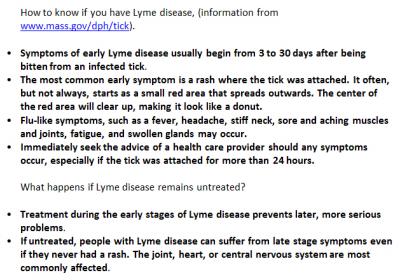

So just how does one protect themselves from a tick? What are the symptoms of Lyme disease? And how do you remove a tick? Check the boxes in the gallery section of this article for answers to those questions with information from the Department of Public Health's website: www.mass.gov/dph/tick.

"Education for a disease, whether it’s a tick borne illness or a mosquito borne illness," said Ethier, "education is the most important for protection."

Wareham resident Mary Nyman is another person who knows a bit about the effects of Lyme disease and the importance of education.

Nyman has been diagnosed with Lyme disease on 3 separate occasions, most recently in the summer of 2011.

Nyman attended a meeting of "Lyme Disease Awareness of Cape Cod," a Mashpee based organization dedicated to spreading awareness of the disease, in early March of this year.

There she learned that May was Lyme disease awareness month and that the organization was putting up lime green ribbons to help raise awareness of the issue.

"It wasn't until I found out they were putting up these green ribbons that I thought, well, nobody is doing this in Wareham," she said.

Now residents can see the bright green ribbons hanging off of trees on the trailheads of Great Neck Wildlife Sanctuary and Lyme disease awareness posters in Town Hall, the Wareham Free Library, and other locations.

"We need more awareness … there needs to be more research done and there needs to be more ways of supporting the treatment for the disease," Nyman said.

Lyme disease in dogs

It is important to protect yourself from Lyme disease, but it is just as important to protect those furry members of the family, namely: your pet dog.

"I really love when people learn about this because [Lyme disease in dogs] so big here on the Cape," said veterinarian and owner of All Pets Medical Center in Buzzards Bay Annette Herbst.

Some of the same rules apply to dogs as to humans. Lyme disease is carried by deer ticks, and needs to be attached to your dog between 12 to 24 hours in order to infect your pet, said Herbst.

Removal should also be done with a pair of tweezers or forceps to prevent infection of the human removing the tick, said Herbst.

But the real goal is preventing your dog from ever getting Lyme disease in the first place, said Herbst. "I think the biggest thing is really just prevention…in the long run you really ensure that your animal stays healthy."

Some of the best preventative measures you can take is to vaccinate your dog or apply topical treatments that will protect against Lyme disease, said Herbst.

• Vaccination is 80 to 90% effective and though not perfect, "that 80% is 80% more than nothing," said Herbst. The vaccination is applied through shots and the first two are done within a month of each other, said Herbst. After that it is a yearly shot between $25 to $35 dollars.

• Topical treatments. "Vectra 3D" is a liquid topical treatment that is applied between the shoulders of your dog and protects your dog for up to 4 weeks, said Herbst. "It also covers fleas which is a big problem this time of year too," said Herbst. Frontline is another topical treatment commonly used.

If your dog does get Lyme disease, treatments are available that can reduce the disease in your pet so that it is no longer a "significant" clinical risk, said Nicole Cummings, veterinarian at Marion Animal Hospital.

But in many cases the bacteria that causes Lyme disease stays within your pet's system, Cummings said. That means that dogs who have had Lyme disease should be tested every year for the presence of the disease.

Sometimes dogs who are retested will not show any symptoms, but will still re-diagnose as positive again, Cummings said.

If that is the case, your dog should be treated for the disease, Cummings said. That's because even if there are no symptoms the disease could develop into a larger problem later on, she said.

For example, dogs who consistently test positive for the disease year after year are at greater risk for developing kidney problems, Cummings said.

Labradors and Golden Retrievers are especially vulnerable to developing kidney problems, said Herbst, and "once Lyme disease goes into the kidneys there is usually nothing you can do," Herbst said.

Why all the information about Lyme disease in dogs but not in cats? Well, Lyme disease has been well studied in dogs, but not in cats, said Herbst, and "until somebody does some more studies" in cats, she said, medical treatment remains focused on dogs.

What to do if your dog gets Lyme disease?

Once your dog gets Lyme disease, look for the following symptoms:

• Loss of appetite. If your dog is not eating right or doesn't look hungry, that's one sign he or she could have Lyme disease.

• Lethargy. Dogs with Lyme disease will not seem lively, such as wanting to go out or greeting you at the door. "They're just a little off," said Herbst.

• Lameness. If your dog is shifting their weight from one leg to the next, that's another sign, said Herbst.

• Fever. One of the biggest signs, said Herbst.

If your dog shows these types of signs, it is best to take him or her to your local veterinarian, who can perform tests such as the Snap 4DX test which also checks for other tick-borne diseases.

If the test comes back positive, your doctor will most likely prescribe doxycycline, a common antibiotic used both in animals and in humans to treat Lyme disease.