Escaped slave made new life, career in Wareham

One of Wareham’s best skippers was a man who escaped slavery.

Linda Ames presented the story of Dempsey Hill’s unlikely journey from enslavement in the South to a career as a pilot in Wareham on Monday night presentation at the Historical Society.

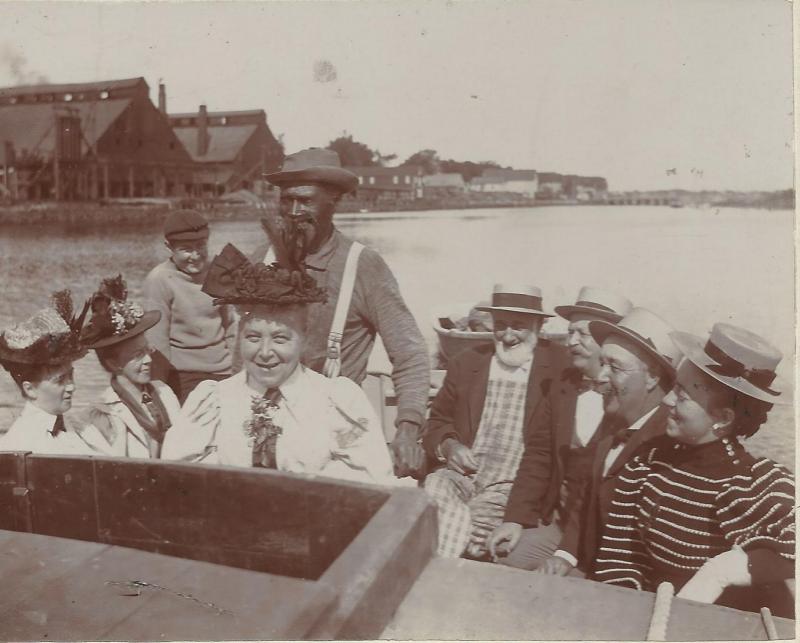

Dempsey Hill, a close friend of Gerard C. Tobey, was known as one of the best and safest pilots in the area in the late 1800s.

Hill was born into slavery in Beaufort, North Carolina, around the year 1842, although his exact birthdate is unknown.

He was chosen by the slave owner to be trained on the riverboats. Hill, a natural on the water, piloted the boats up and down the rivers, and gained familiarity with the geography and the layout of the town, as he was allowed to run errands. Ames said that his position likely allowed Hill to gain more knowledge about the goings-on in the world outside the plantation.

When Hill was about 20 years old, he saw his chance to escape. It was about ten months after the start of the Civil War, and, on August 27, Union troops captured nearby Fort Hatteras.

Hill knew the time was right. Along with four friends, Hill snuck out one night to the customs house in town where he stole extensive charts for navigating the waters near Beaufort. The group buried the charts in a nearby cemetery for safekeeping. Several nights later, they dug up the charts and piloted a riverboat to the USS Bresalier. He and his friends presented the captain with the charts and their skills as pilots, and asked to join the Navy.

The Captain said that they could join if the charts were legitimate, and, in the meantime, held them in the bottom of the ship. He said that if the charts were false, the men would be executed.

After verifying the charts’ authenticity, Hill and his friends were accepted into the Navy.

Throughout his service on several ships, Hill was described as a “gallant and fearless sailor.” He endured several injuries, however, including being knocked from the forecastle to the main deck, where he seriously sprained an ankle, and being struck in the small of his back by the recoil of a gun. Following the second injury, he was treated for weeks before being discharged from the Navy as a free man in Washington, DC.

From there, Hill traveled to New York City and worked on coastal trading vessels that traveled between New York and Cape Cod.

In 1867, Hill moved to Wareham. He lived in a tenement house on Main Street, located roughly where Cumberland Farms stands today.

Hill was one of three people of color in Wareham at the time. He initially worked at an iron mill -- likely the one known today as Tremont Nail -- and he soon married a woman from New Bedford named Mary Dandrich. Mary soon gave birth to a son named Enoch Andrew Hill.

Sadly, Enoch died at fifteen months, and, some time after the baby’s death, Mary was committed to the Taunton Asylum for the insane, where she died four years later.

It was then that Hill returned to the water.

He leased vessels and led chartered boating and fishing trips.

At one point, he was was struck to see someone he recognized from his past. One of the deckhands on a trading vessel in the Narrows was someone he had known as a toddler and child -- the son of his former slaveholder. The two spent time together catching up in Hill’s home.

In Wareham, Hill had become close friends with Gerard C. Tobey, as well as members of other prominent Wareham families.

Tobey and Hill had bonded over their mutual love of fishing and boating. Tobey knew Hill was saving up to buy his own catboat, because he had often waxed poetic about the specifications of the vessel and how it was his greatest dream to own his own vessel and captain it.

One day, Hill was led to the waterfront where he saw the boat, exactly as he had described it. Tobey had purchased the vessel for him as a gift -- and named it “Dempsey’s Dream.”

Hill was very involved with the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization for veterans who served in the Union Army during the civil war.

Taking great pride in his service, Hill was known for wearing his uniform whenever possible and attending every parade and event.

In September 1892, he attended the National Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic. At some point on that journey, he met Cecilia Shaw of Alexandria, Virginia, and they agreed to get married.

Shaw returned with him to Wareham and they got married. Shaw became pregnant.

Around this time, Hill’s health began to fail, due perhaps in part to the injuries he sustained during the war.

Tragically, Hill died one month before his daughter, Carrie Dempsey Hill, was born.

Hill’s death was noted in six papers, including the New York Herald and a paper in Lake Erie, Pennsylvania.

That Hill was memorialized in so many papers demonstrates how well-known he was, Ames said. However, there was no mention in any of the papers of any funeral or memorial services for Hill, which Ames said was very unusual for the time. Hill is buried in Centre Cemetery.

After Hill’s death, Cecilia and her daughter Carrie moved back to Virginia to live with her family.

Ames questioned why Hill was so quickly forgotten in Wareham.

“What about the man who goes quietly through life?” she asked. “To say he was a treasured asset during the twenty years he was here is an understatement.”